By Michail Saouach, Junior Analyst KEDISA

Canada has been a member of NATO, since the establishment of the organization in 1949. During their membership, Canadians have taken part in several NATO operations, providing military assistance. Some of the operations in which Canada is currently enrolled are listed in the table below.

Current NATO operations in which Canada is participating

| Name | Location |

| Operation IGNITION | Reykjavik, Iceland |

| Operation KOBOLD | Kosovo |

| Operation REASSURANCE | Central & Eastern Europe |

| Operation IMPACT | Syria & Iraq |

| Operation SEA GUARDIAN | Mediterranean |

Source: Government of Canada, canada.ca

In all the aforementioned operations, Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) contribute to common military exercises by conducting explorations of explosive materials and thus, controlled detonations, by providing headquarters and logistic support, air surveillance (for instance, radar tracking), by participating in helicopter air detachments and gathering intelligence[1]. The main purpose of these large-scale military contributions is to promote international peace, security and stability, as stipulated by the Articles 2 and 3 of the North Atlantic Treaty[2], effective collaboration among nations in terms of military capabilities and the building of powerful and long-standing bilateral relations.

Furthermore, it is worth noting the release of the new Canadian defence policy “Strong, Secure, Engage” in June 2017 by the Minister of National Defence, Mr Harjit Sajjan. It is a well-designed, ambitious policy plan, which aims to maximize Canada’s defence capabilities in order to be more resilient in the global security environment, which is marked by the changing nature of conflict and the growing use of technology in terrorist attacks (cyberterrorism). The significant importance of this plan can be noticed from the pledge of the Canadian government to “grow defence spending from $18.9 billion in 2016-17 to $32.7 billion in 2026-27”[3]. Obviously, NATO is a crucial part of this policy. Canada will invest a considerable amount of money in order to fulfil the governmental commitments to NATO. For instance, $26.4 billion will be funded in equipment projects for Canadian Air Forces and will allow to Canada “to deliver on NORAD and NATO commitments”[3]. Interoperability, intelligence sharing, support to NATO allies and the growth of the country’s global presence in multilateral organizations will be top priorities for the Canadian government.

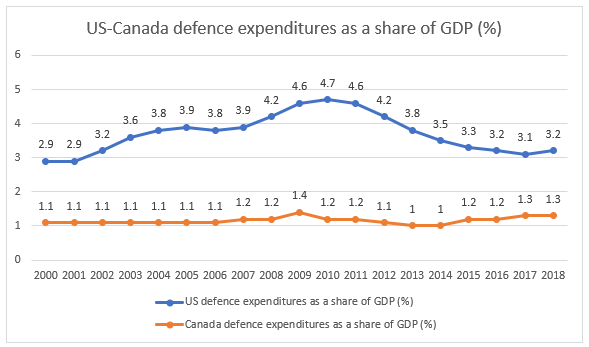

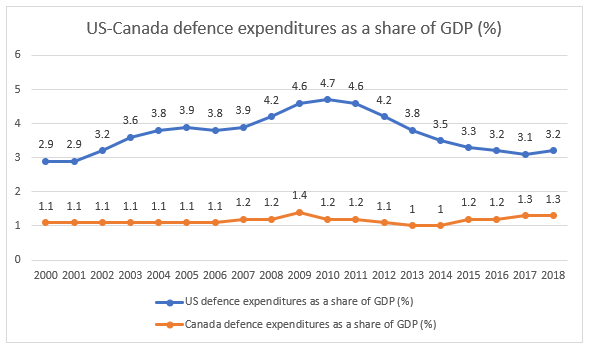

Notwithstanding the participation of Canada in NATO missions and the rearrangement of national defence policy, the budget problem remains of significant importance and a thorny issue in US-Canada relations in the context of NATO. According to the Wales Summit Declaration in 2014, NATO members are expected “to spend a minimum of 2% of their GDP on defence”[4]. As can be seen, by the line graph below, Canada has contributed less than the anticipated amount of money from the beginning of the 21st century until 2018.

Source: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, sipri.org

In general, Canada’s defence expenditures remained stable and significantly lower than two per cent over the examined 18-year period, with a peak of 1,4% in 2009. On the other hand, the expenditures of the United States rose from 2,9% in 2000 to 4,6% in 2009 and peaked at 4,7% in 2010. During the second decade of the twenty-first century, a downward trend can be noticed in the US defence investments, however, never dropped below 3,1% (in 2017) [5]. Overall, the percentage of the United States defence expenditures as a share of their GDP remained considerably higher than the 2% of NATO guideline and in some cases, it was more than double. At the same time, Canada’s percentage as an average was slightly higher than 1%.

At the 2018 Brussels Summit, the budget issue was raised by President Donald Trump[6], who claimed that the United States has overpaid for the security of other states, including Canada[7]. The data, provided by the graph above, can justify to some extent Trump’s view. Only seven countries[8] meet successfully NATO budgetary obligations, while the organization is composed of 29 member states. With regard to Canada, some argue that the quality of its contributions outweighs the budget problem. It is quite uncertain whether the 2% target can be considered as a reliable measure of a country’s military capability or not. There is a significant difference in the way that states calculate their defence expenditures, with a considerable amount of money spent on various “paramilitary organizations” and pensions for retirees[9], instead of major equipment and research. Regardless of the reliability of budget calculations, Canada has provided considerable assistance to NATO in terms of non-financial contributions, by taking part in multiple operations and by providing personnel to the alliance[9]. According to a research survey, conducted by Pew Research Center, NATO is quite favorable among Canadians, with 66% having a positive opinion of the alliance[10]..

The Arctic as a milestone in Canadian foreign policy

The Arctic is situated in the northern hemisphere of the Earth, more specifically “between the North Pole and the northern timberlines of North America and Eurasia”[11]. In this polar area of the planet, 8 countries, the so-called “Arctic States”[12], have territory: Finland, Sweden, Norway, Iceland, Denmark (Greenland), Canada, the United States and Russia. Arctic Canada includes more than 40% of the whole country and the majority of its marine coastlines[9]. The Arctic plays a vital role in Canada’s defence and foreign policy.

First of all, the main element, which makes the Arctic extremely important, is its rich natural resources and the potential undiscovered ones. According to an assessment conducted by the United States Geological Survey (USGS), some areas in “Canada, Russia and Alaska […] account for approximately 240 billion barrels (BBOE) of oil and oil-equivalent natural gas”[13]. Furthermore, many areas in the Arctic, particularly offshore, are undiscovered in regard to petroleum. The results of this assessment showed that in the Arctic “the total mean undiscovered conventional oil and gas resources are estimated to be approximately 90 billion barrels of oil, 1,669 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, and 44 billion barrels of natural gas liquids”[13]. Those tremendous amounts of natural resources can justify the importance of this area on the global scene and the effort of the Canadian government to claim the Northwest Passage as part of its internal waters[9].

In addition, global warming leads to the melting of polar ice and thus, makes the access of vessels easier in the area. This increases the prospect of global trade and maritime capabilities because it could reduce significantly the time spent in travelling from Asia to Europe[9]. As a result, the Chinese interests in the area are growing rapidly, because the Arctic could constitute a valuable part of its contemporary Silk Road[9]. Simultaneously, Russia promotes its militarization in the Arctic, by improving its military equipment (use of submarines) and the ability to conduct operations in the area[9]. For those reasons, Canada should seek a solution in the context of NATO, such as the participation in common military exercises, which will improve the CAF’s capability and will ensure the leadership role of Canada in the area. Furthermore, closer co-operation with European NATO allies, especially with the Arctic neighbors, and the construction of a modernized and well-designed North Warning System[i] will be proved quite helpful in the effort to deal with the emerging powers and the new security environment in the Arctic[9].

Sources

- Government of Canada, “Current Operations List”, Available at https://www.canada.ca/en/ department-national-defence/services/operations/military-operations/current-operations/list.html (Accessed: 26 November 2018)

- The North Atlantic Treaty (1949), Available at https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/ pdf/stock_publications/20120822_nato_treaty_en_light_2009.pdf

- Canadian Armed Forces (2017), “Strong, Engaged, Secure”: Canada’s Defence Policy, Available at http://dgpaapp.forces.gc.ca/en/canada-defence-policy/docs/canada-defence-policypdf

- The Wales Summit Declaration (2014), Available at http://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/

2014_2019/documents/sede/dv/sede240914walessummit_/sede240914walessummit_en.pdf

- Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, “Military expenditure by country as a percentage of gross domestic product, 1988-2018” (2019), Available at https://www.sipri.org/ sites/default/files/Data%20for%20all%20countries%20from%201988–2018%20as%20a%20share%20of%20GDP%20%28pdf%29.pdf

- The White House, “Remarks by President Trump and NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg at Bilateral Breakfast” (2018) Available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefingsstatements/remarks-president-trump-nato-secretary-general-jens-stoltenberg-bilateral-breakfast/

- John Paul Tasker (2018), “Trump says NATO allies like Canada are ‘delinquent’ on military spending. Is he wrong?”, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Available at https://www.cbc.ca/ news/politics/trump-nato-allies-delinquent-military-spending-1.4742588

- North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2012-2019)” (2019) Available at https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/ pdf_2019_06/20190625_PR2019-069-EN.pdf

- House of Commons of Canada (2018), “Canada And NATO: An Alliance Forged In Strength And Reliability”, Report of the Standing Committee on National Defence, Available at https:// ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/NDDN/Reports/RP9972815/nddnrp10/ nddnrp10-e.pdf

- Moira Fagan (2017), “NATO is seen favorably in many member countries, but almost half of Americans say it does too little”, Pew Research Center Spring 2017 Survey Available at https:// pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/07/09/nato-is-seen-favorably-in-many-member-countriesbut-almost-half-of-americans-say-it-does-too-little/

- Company, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing. “The American Heritage Dictionary entry: arctic”. ahdictionary.com.

- The Arctic Council (2015), “Member States” Available at https://arctic-council.org/index.php/ en/about-us/member-states

- United States Geological Survey (2018), “Circum-Arctic Resource Appraisal: Estimates of

Undiscovered Oil and Gas North of the Arctic Circle” Available at https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/ 2008/3049/fs2008-3049.pdf

- Raytheon Company, “North Warning System” Available at https://www.raytheon.com/ ourcompany/global/americas/canada/nws

[i] A joint United States and Canadian warning radar system for the air defence of North America. Available at https://www.raytheon.com/ourcompany/global/americas/canada/nws